In the late hours of October 23, Craig Clements was grading papers when a colleague in Oakland texted him about a rapidly growing wildfire just north of San Francisco. He texted a few of his students, who jumped out of bed and rushed his way. Together they loaded a radar-packing Ford F-250 pickup with gear and hit the road, gathering the Oakland colleague on their way to the Kincade Fire, which would quickly become California’s biggest blaze of 2019.

Clements, a fire weather researcher at San Jose State University, and his team arrived around 1 am, driving past fire engines and evacuating locals as they steered toward the blaze. Normally they’d check in with an incident command post first, where officials could tell them where the wildfire might be heading, but the conflagration was still too young and chaotic for such organization. So they drove on, trying to position themselves near but not too near the growing plume, searching for a spot not surrounded by brush or traffic, away from power lines that could fall on their heads. On their map they found a road leading to a vineyard—lots of vegetation, sure, but chock full of water and therefore quite resistant to burning—and turned in, landing a kilometer from a ridge line the fire was burning up to.

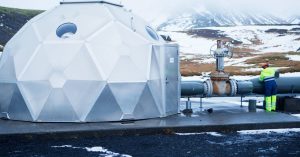

Jacks level the vehicle in a matter of minutes.

Photograph: SJSU Fire Weather Research LaboratoryIt was perfect: good visibility, out of harm’s way, and most of all, well positioned for their equipment. Amid falling ash and fierce winds, they set up their mobile lab. With the press of a button, jacks automatically leveled out the vehicle, bringing online the only mobile radar in the western US. The sciencing of the Kincade Fire had begun.

A wildfire is a phenomenon of almost impenetrable complexity. Different kinds of brush burn at different rates, and even the same kind of brush can burn differently depending on hydration and humidity, which change hour by hour. Topography affects the trajectory of a fire, as does wind. For Clements, the goal is to better understand how wildfires can create their own weather and how the dynamics of the plumes affect the fire’s spread.

“Everybody on Twitter is an expert on wildfire science, but nobody’s actually been to one,” Clements says. “We’re the only meteorological team in the United States with this capability, because we’re fire-line qualified.” They go through special training and carry special equipment that could save their lives, like fire shelters. “It’s like a foil bag that you wrap your body in. And you get down on the ground and you hope to hell that you don’t need it.”