North of Silicon Valley, protected by the Point Reyes National Seashore, is the only operational ship-to-shore maritime radio station. Bearing the call sign KPH, the Point Reyes Station is the last of its kind.

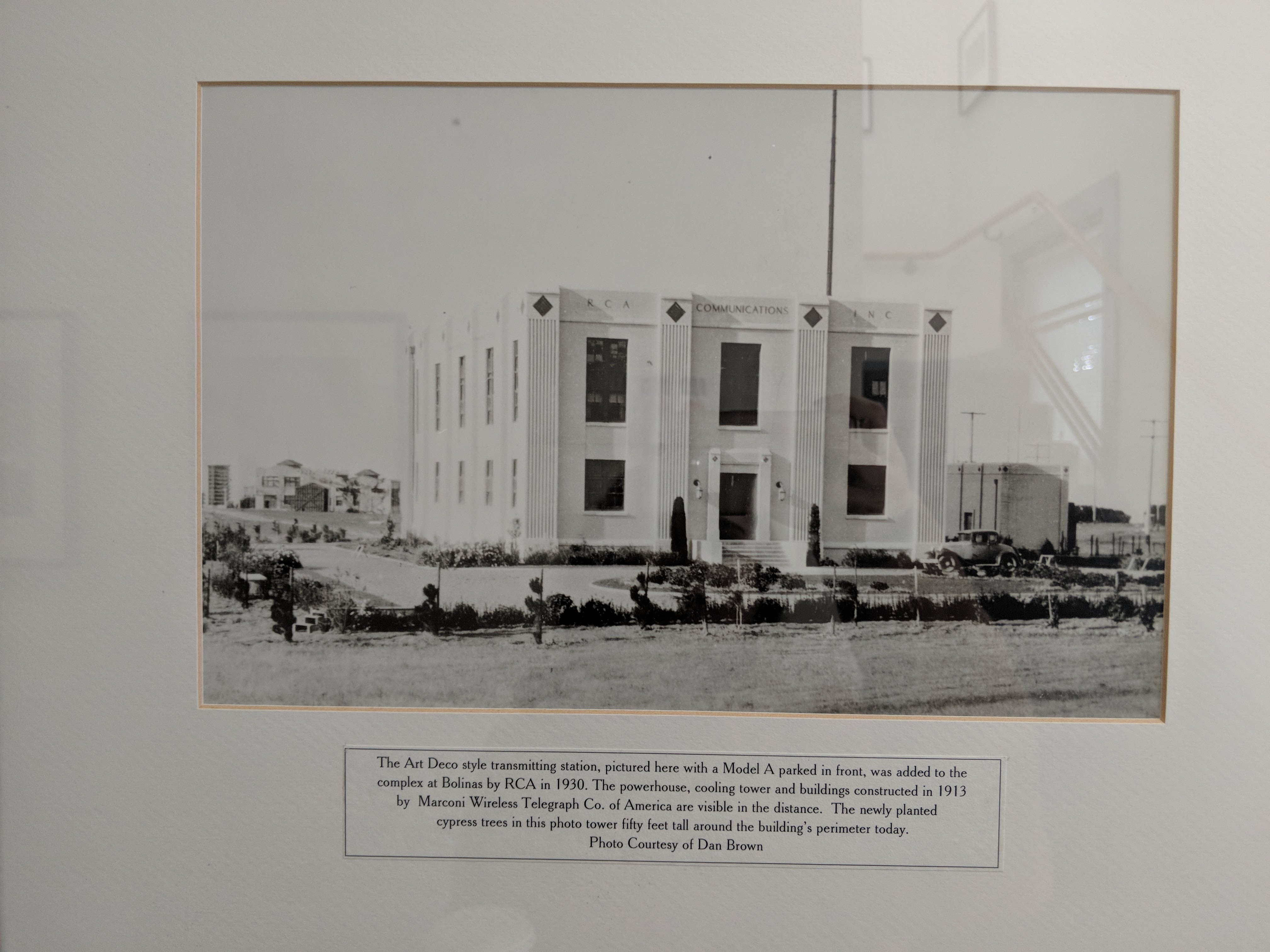

KPH is divided between two physical stations: one, knows as the voice, is responsible for transmitting; the other half of the station, known as the ears, was where human operators listened for incoming messages. The voice is located 11 miles north of Point Reyes in the small town of Bolinas, Calif., and the ears reside within the Point Reyes National Seashore boundary nestled in pastures full of cattle and backdropped by the Pacific Ocean.

Stations like this once riddled the California coastline as part of a radio communication network. The operators who ran them were charged with watching over the Pacific Ocean airways, relaying messages to the sailors at sea.

“These guys and women were the best there were, and they had to be,” says Richard Dillman, chief operator at the Maritime Radio Historical Society. “On the ships, you could get away with anything. You could send slow, you could send fast, you could send like you were drunk, you could send like you are beating two spoons together. At the shore side, you had to be able to say, ‘fine, I got it, you can send fast, no problem. Send slow, I’llwait. Send like you are drunk, I can understand you.’ Because every word is revenue for the company because you were charging by the word.”

Dillman, who was never an employee of KPH, but rather a self-described “groupee and radio-obsessed person,” says the operators had to adapt to anything. “They were the best there were. They are our heroes and heroines.”

But once satellite communication became cheaper than paying radio operators, telegraphy became obsolete, and the network of radio stations became all but lost, as they were abandoned, sold and scavenged for parts.

Marin County Congressman Clem Miller saved KPH from this fate by writing and introducing the bill for the establishment of Point Reyes National Seashore. The bill preserved the land from development after operations ended.

A telegraphic timeline

The communications industry in the U.S. has seen several waves of disruption. The first significant innovation was sending a message by transmitting electrical signals over a wire.

In 1843, Samuel Morse, the father of Morse code, received funding from Congress to set up and test his new communication wire from Washington, D.C., to Baltimore. Upon completion, he sent the first official telegraph saying, “What hath God wrought.” What it wrought was money.

Morse received enough funding to string wire across an unsettled American landscape. From 1843 to 1900, wired telegraphy reigned until a new technology disrupted the communication monopoly of Western Union.

On June 2, 1896, Guglielmo Marconi patented a system of wireless telegraphy that would utilize radio waves to transmit Morse’s dits and dahs, making wired communication seem infrastructure-heavy. Plus, wireless telegraphy made maritime and transcontinental communication a lot more simple.

For almost 100 years, Morse code was used to communicate with ships at sea. By 1999 the industry had switched over to the cheaper and more efficient satellite communication systems.

The Point Reyes KPH station ended operations on June 30, 1997. The last day of U.S. commercial use of Morse code was July 12, 1999. The final message sent was the same as Morse’s first: “What hath God wrought.”

‘This was the end’

“It’s just beeps in the air,” says Dillman. “That is all Morse code is. And yet it was so impactful and emotional to these people,” he says about the operators and sailors he was with during the last day of Morse. “Because here they are seeing their career, their way of life, their skills disappearing. This was the end of the line. It used to be that you could take your license and telegraph key and move onto the next station, get a job, no problem. This was the end.”

After the last day of Morse in 1999, two years after KPH shut down, Richard and a few other radiomen drove up to the shuttered KPH station to assess how harsh the elements had been in the two years since it closed.

“Here it was, our life’s work, just handed to us,” Dillman says. “Because here are the ears, in Point Reyes, still living. The voice in Bolinas — dark and cold, but existing. So all we had to do was convince the park service that [restoring the station] was worth doing, and we were the guys to do it. And we are still amazed that they bought our story, and we have not turned back.”

Dillman and the rest of the radio squirrels that hang around KPH can be found every Sunday and more than welcome visitors.