David Friend is the CEO of cloud storage company Wasabi, and co-founder of cyber security company Carbonite, recently bought for $1.4 billion. Wasabi is his sixth startup.

There has been a mountain of press lately about how investors are souring on unprofitable unicorns.

We’ve seen this movie before; for a while, it’s all about growth, and profits be damned, then the winds change, and everyone focuses on “capital efficiency,” or similar jargon meaning, “how can I get big returns without having to put much money at risk?”

The winds blow back and forth. Until very recently, everyone was in love with consumer unicorns again. Now investors are licking their wounds, except for those who eschewed the name brands and went for boring old B2B and infrastructure companies. They are doing just fine, thank you.

Why are investors overpaying for household-name unicorns? Is it that they really believe they are good assets, or are other factors at play? The fact is that venture funds and private equity funds are competing for investment funds themselves. I am personally an investor in several venture funds, and I have heard the pitch, “we were investors in Facebook, Instagram, Uber, Twitter (or whatever), and we can get you access to these deals.” Sounds good, but what they don’t tell you is how much they paid (or overpaid) to be part of these deals. It’s such nonsense and the perennially poor returns delivered by the ego-driven venture capital industry are its just rewards.

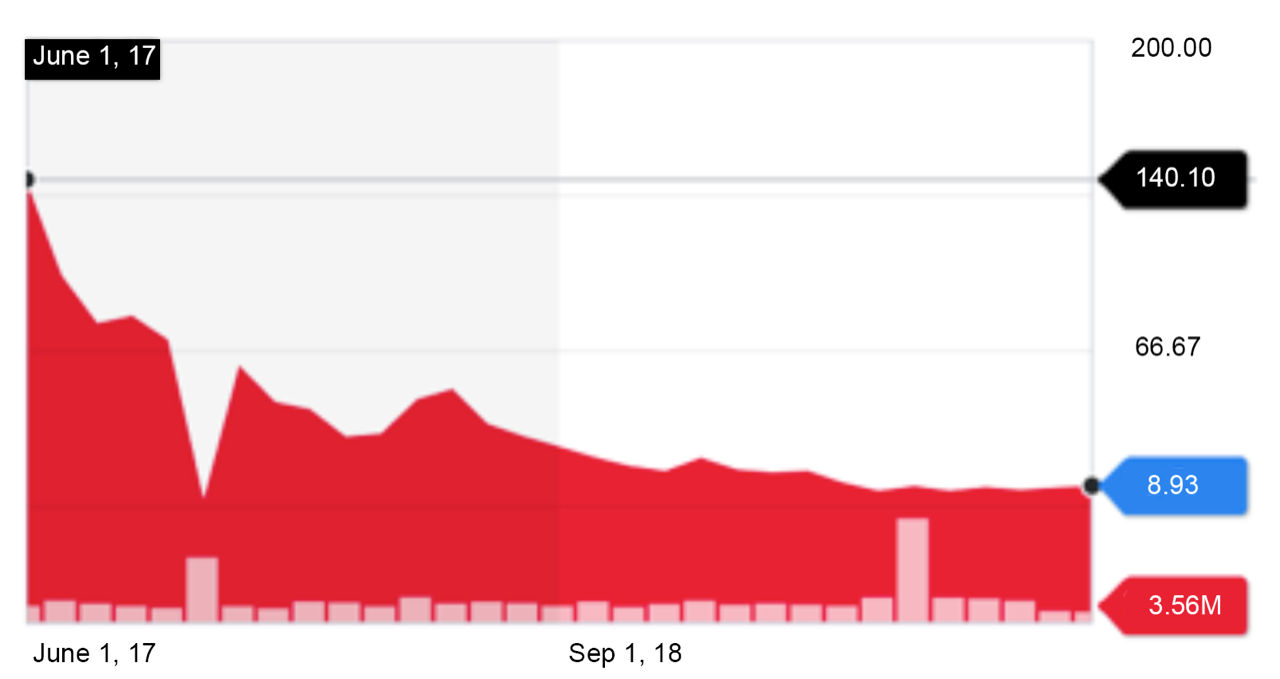

Downward stock valuations of unicorns post-IPO. (Yahoo Finance)

Investors who bid up the valuations of high-profile unicorns are of course hoping that an IPO will eventually bail them out. The problem is that public fund managers, like Fidelity or Blackstone, who control most of post-IPO stocks, look at the value of a company quite differently. They see a company’s “value” as the sum total of all the company’s future profits. They can’t offer their clients “exclusive” access to hot deals. We’re talking public stocks that anyone can buy.

If nobody can see a clear road to profitability, then this hard-nosed approach to valuation will lead to stocks tanking after an IPO. That’s recently been the case with We, Uber, and numerous others.

From 2010 to the first quarter of 2015, investors collectively poured $9.4 billion into the on-demand economy, according to data from CB Insights. Uber accounted for 58% of the $4.12 billion raised in 2014. What’s also striking is how quickly the industry piled onto the latest thing between 2013 and 2014. Since its IPO in May of 2019, Uber’s stock has fallen nearly 40% from its peak, Lyft is down even more, and Softbank’s most recent investment in We appears to have wiped out nearly 80% of its previous private valuation. Masayoshi Son has been publicly apologizing for his investment in We: “My investment judgment was poor in many ways,” said Son.