With iOS 12 last year, Apple’s big theme was stability. It’s not like there were no new features, but the real draw was that older devices might run a little better. This time is, a little different. iOS 13 is heavier on the new additions, perhaps to the detriment of its overall stability.

iOS goes dark

The most immediately noticeable change here is the dark mode, which drapes iOS in black. What can I say? It’s pretty enough that I’ve been using it from the moment I installed the first beta, and there’s no turning back. But, a quick toggle is all it takes to switch between the light and dark looks if you prefer variety, and an automatic mode tells iOS to switch between the two at the right time of day.

Dark mode has some fringe benefits too, like the fact that it could lead to some battery savings on iPhones with OLED screens. (That’s the X, XS, XS Max, 11 Pro, and Pro Max.) It’s difficult to gauge exactly how much power you could save, and realistically you’re only gonna see extra minutes, not extra hours of use. No, the real reason to embrace dark mode is that you like the way it looks, or don’t want to strain your eyes in dim light.

I do have to give Apple credit for consistency. When Android 10 launched, many of Google’s most heavily used apps — including Gmail! — didn’t support the update’s system-wide dark mode. By comparison, nearly all of Apple’s preloaded apps switch color schemes when asked. The biggest exception I’ve seen so far is Apple’s iWork suite, which (at the time of writing) hasn’t been updated in about three months. This is a notable omission no matter how you look at it, but it seems pretty clear that with iOS 13, Apple had some more pressing concerns to deal with.

New (and better) privacy tools

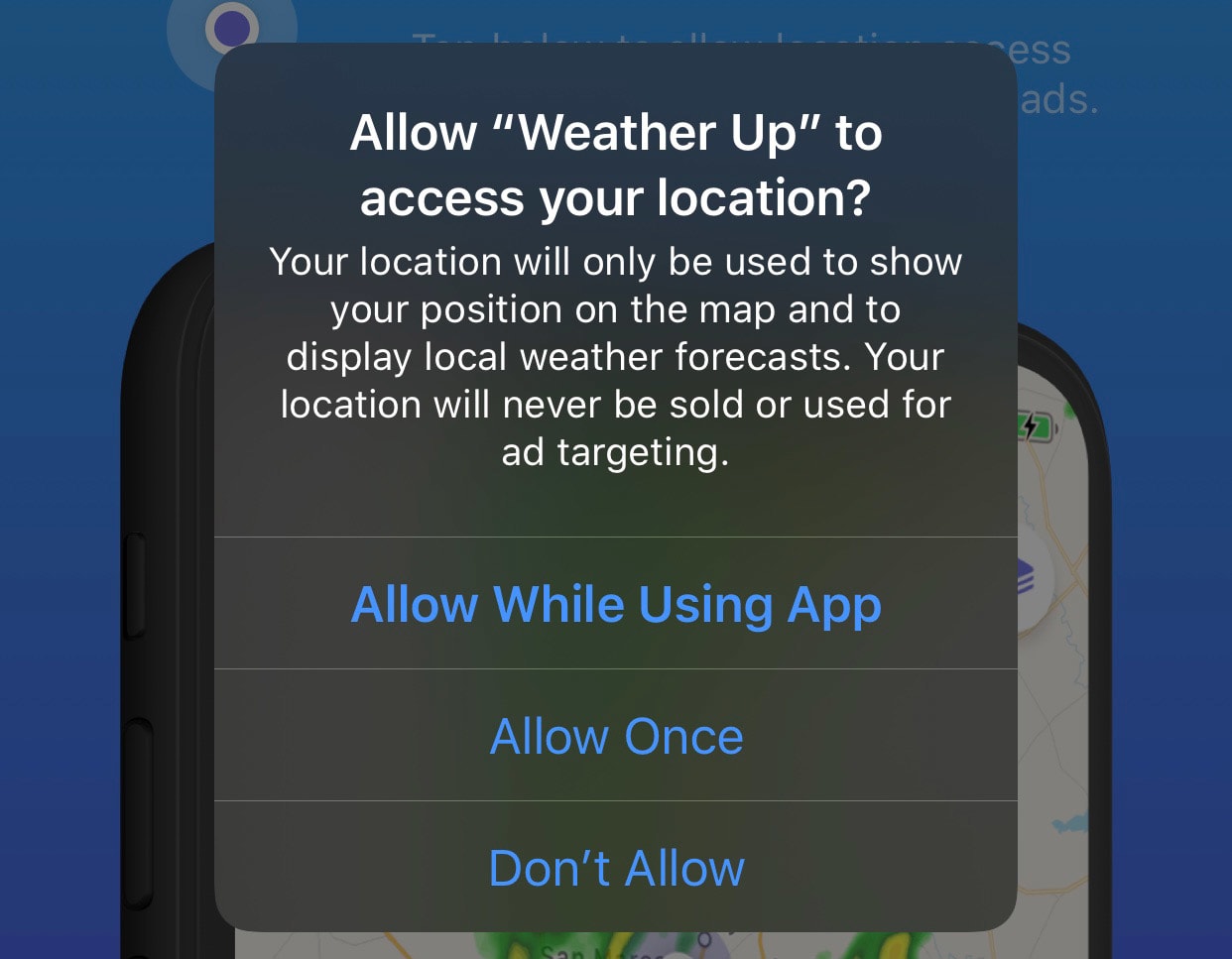

You might not use dark mode, but I guarantee it won’t be long until you run into Apple’s privacy tools, like iOS 13’s more aggressive location permission controls. In this case, “aggressive” is a good thing. It used to be that, when you downloaded and ran an app that wanted to see where in the world you were, you’d typically get three choices: don’t allow, always allow, or allow while the app is actively being used. iOS 13 handles things a little differently.

This year, that “always allow” option is gone. Sort of. It’s been relegated to individual apps’ location settings, so you have to go out of your way to give it unfettered access. You can also now effectively say “OK, just this once.” After some time elapses, permission is revoked, and you can go about your day knowing there’s one less bit of software following your every move. The new option has been great when using apps I know I’m probably not going to touch again for a while, and the mild annoyance of re-allowing access is a small price to pay for a little more privacy.

Apple also changed the way it reminds you when an app has had prolonged access to your location. This time around, in addition to a (fairly bland) description, iOS 13 shows you a tiny map highlighting every instance where the app in question locked onto you. More often than not, my results would look like a mottled blue worm connecting the dots of a day’s travels. (Facebook is especially bad at this, which perhaps explains why it wanted to warn people about the changes Apple was making in advance.)

I only wish Apple’s other big privacy feature was as pervasive. Eventually, you’ll be able to sign into apps and services across the web with your Apple ID — the trick is, those apps and services won’t ever see your Apple ID. Instead, iOS will create a new account with a strong password and a dummy email that forwards all the pertinent materials to wherever you want it. It sounds great on paper because it is. Sign in with Apple, as it’s called, makes onboarding super-fast and protects you in case of an all-too-common data breach.

The only problem is, there’s a decent chance the apps the services you’d want to use this with don’t support it yet. Actually, at this point, hardly any apps do. I’ve used it to create secure accounts on Kayak and WordPress in just a few moments. Beyond that, though, pickings are slim. That will change because Sign in with Apple is meant to be mandatory for all services that have an account system, even if they just let you log in with Facebook, Google, or Twitter. The thing is, Apple hasn’t set a hard deadline for compatibility, so it’s anyone’s guess whether developers will embrace Apple’s approach in the short term.