This morning, the Justice Department announced that it had brought charges against the administrator and hundreds of users of the “world’s largest” child sexual exploitation marketplace on the dark web.

For me, it marked the end of a story I’ve wanted to write for two years.

In November 2017, I was working for CBS as the security editor at ZDNet. A hacker group reached out to me over an encrypted chat claiming to have broken into a dark web site running a massive child sexual exploitation operation. I was stunned. I had previous interactions with the hacker group, but nothing like this.

The group claimed it broke into the dark web site, which it said was titled “Welcome to Video,” and identified four real-world IP addresses of the site, said to be different servers running this supposedly behemoth child abuse site. They also provided me with a text file containing a sample of a thousand IP addresses of individuals who they said had logged in to the site. The hackers boasted about how they siphoned off the list as users logged in, without the users’ knowledge, and had more than a hundred thousand more — but they would not share them.

If proven true, the hackers would have made a major breakthrough in not only discovering a major dark web child abuse site, but could potentially identify the owners — and the visitors to the site.

But at the time, we could not prove it.

My then editor-in-chief and I discussed how we could approach the story. A primary concern was that the dark web site was already under federal investigation, and writing about it could jeopardize that effort.

But we also faced another headache: There was no legal way we could access the site to verify it was what the hackers claimed.

“Children around the world are safer because of the actions taken by U.S. and foreign law enforcement to prosecute this case and recover funds for victims.”

Jessie K. Liu, U.S. Attorney for the District of Columbia

The hackers gave me a username and password for the site, which they said they had created just for me to verify their claims. But we could not access the site for any reason — even for journalistic reasons and in a controlled environment — for fear that the site may display child abuse imagery. Only federal agents working an investigation are allowed to access sites that contain illegal content. While journalists have a lot of flexibility and freedoms, this was not one of them.

After a call with several CBS lawyers, we decided that there was no legal way to write the story without verifying the site’s contents, something we legally weren’t able to do.

The story was dead, but the site wasn’t.

One thing the lawyers couldn’t tell me is if I should report the findings to the government. That was ultimately my decision to make. It’s a bizarre situation to be in. As a cybersecurity and national security reporter, the government all too often is “the nemesis,” often a target of journalistic inquisitions and investigations. But while journalists are told to report and observe and not get involved, there are exceptions. Risk to life and child exploitation are top of the list. A journalist cannot idly stand by knowing there could be a car bomb sitting outside a building, ready to detonate. Nor can one dismiss the idea of a child abuse site continuing to operate on the dark web.

I spoke with a well-known journalist to ask for ethical advice. We agreed to speak on background, from reporter to reporter. Having never faced a situation like this, my primary concern was to ensure I was on the right moral, ethical and legal side of things. Was it right to report this to the feds?

The answer was simple and expected: Yes, it was right to report the information to the authorities, so long as I protected my source. Protecting your sources is one of the cardinal rules of journalism, but my source was a hacker group — it was not the dark web site itself. After all, I was working under the assumption that the authorities would not care much for the source information anyway.

I reached out to a contact at the FBI, who passed me on to a special agent at a field office. After a brief phone call, I emailed the four IP addresses slated to be the dark web site’s real-world location, and the list of the thousand alleged users of the site.

And then silence. I heard nothing back. I followed up and asked, but the agent warned that if the site became — or was already — subject to investigation, there was little, if anything, they could say.

I recall the hackers were frustrated. After I told them I wouldn’t be writing the story, we are no longer communicating.

Weeks went by. I felt just as frustrated at the lack of insight into what I had only guessed or hoped was progress by the federal agents.

I recall running the list of IP addresses that the hackers gave me through a resolver, which provided some limited insight into who might be visiting the dark web site. We found individuals access the dark web site from the networks of the U.S. Army Intelligence, the U.S. Senate, the U.S. Air Force and the Department of Veterans Affairs, as well as Apple, Microsoft, Google, Samsung and several universities around the world. We could not identify, however, specific individuals who accessed the site. And because the dark web is anonymized, it’s likely that not even companies knew their staff were accessing this site.

How could they possibly let this go, I thought to myself, wondering whether the FBI agent had acted on the information I handed over. If there was an investigation it would take time and effort, and the wheels of government seldom move quickly. Would I ever know whether the perpetrators would ever be caught?

Today, two years later, I got my answer.

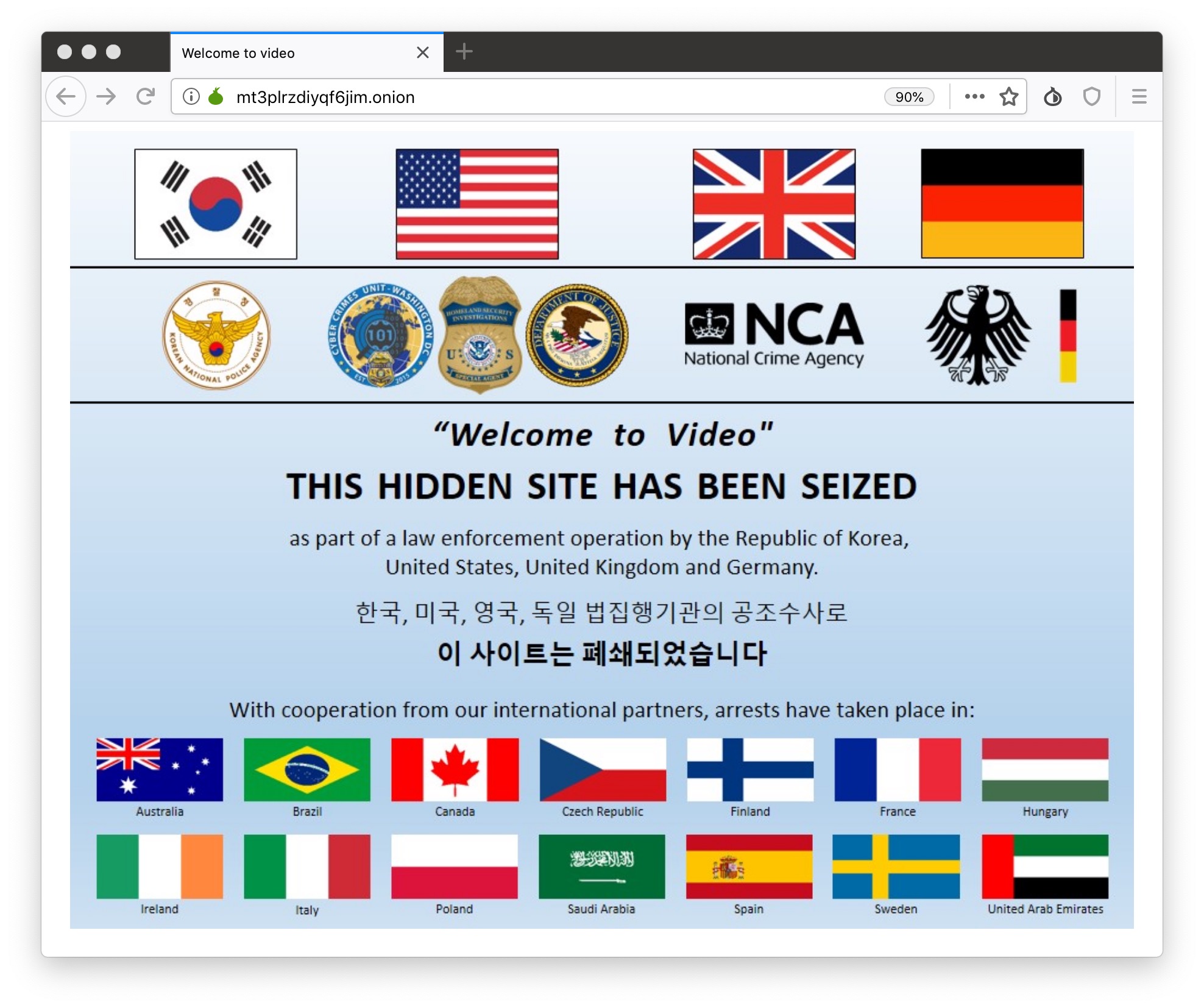

The seized dark web marketplace, containing 250,000 child sexual exploitation videos and images. The site was shut down following a government investigation.

U.S. prosecutors said in the indictment, filed in August 2018 but unsealed Wednesday, that the dark web site — confirmed as “Welcome to Video” — had some 250,000 user-uploaded graphic images and videos of children who were being sexually abused. The government called it the “largest darknet child pornography website” in a press release.

This morning, after news of the site’s removal had been reported, I rifled through the documents posted on the Justice Department’s website and found a screenshot of the site, with the full web address in the address bar. It was a match. For the first time since the hackers told me of the dark web site, I went to the Tor browser and pasted in the address. It loaded — with the government’s “website seized” notice staring back at me.

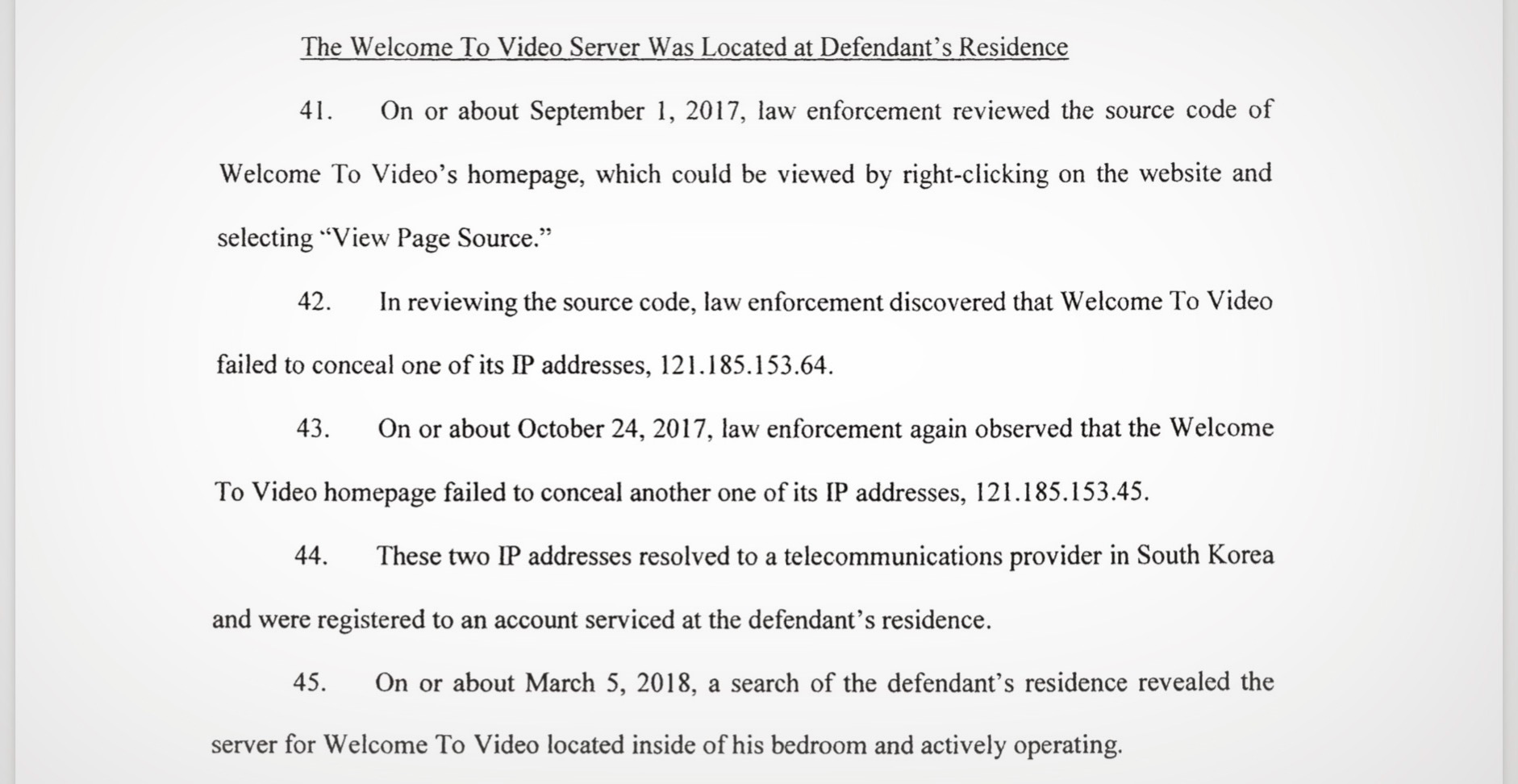

According to the indictment, federal agents began investigating the site in September 2017, two months before the hackers breached the site. The site’s administrator, Jong Woo Son, had been running the operation from his residence in South Korea since 2015. The indictment said the main landing page to the site contained a security flaw that let investigators discover some of the IP addresses of the dark web site — simply by right-clicking the page and viewing the source of the website.

It was a major error, one that would trigger a chain of events that would ensnare the entire site and its users.

Prosecutors said in the indictment that they found several IP addresses: 121.185.153.64 and 121.185.153.45. One of the IP addresses the hackers gave me was 121.185.153.114 — an address on the same network subnet as the dark web site.

It was long-awaited confirmation that the hackers were telling the truth. They did in fact breach the site. But whether or not the government knew about the breach remains a mystery.

The IP addresses in the recently unsealed indictment were on the same network as the IP address provided by the hackers. (Image: TechCrunch)

Some five months after I contacted the FBI, the government obtained a warrant to seize and dismantle the dark web site. It’s believed the indictment was kept under seal until today in order to arrest, charge and prosecute individuals suspected of being involved in the site.

In total, there were 337 arrests, including a former Homeland Security special agent and a Border Patrol officer.

Authorities were able to rescue 23 children who were being actively abused.

I reached out to the federal agent this morning, and was told the FBI was not involved in the investigation. The Internal Revenue Service’s Criminal Investigation division, which investigates and prosecutes financial crimes, and the Homeland Security Investigations unit, which largely deals with human smuggling, child trafficking and related computer crimes, were credited with the work.

While authorities from the U.K. and South Korea contributed to the investigation, sources say the IRS received an anonymous tip that kickstarted it.

From there, the IRS used technology to trace bitcoin transactions, which the dark web site used to profit from the child exploitation videos. Users would have to pay in bitcoin to download content or upload their own child exploitation videos. The government also launched a civil forfeiture case to seize the bitcoins allegedly used by 24 individuals in five countries who are accused of funding the site.

The hacker group has not been in touch since we broke off communications. Publishing a story about the hack two years ago may have caused irreparable harm to the government’s investigation, potentially sinking it entirely. It was a frustrating time, not least being in the dark and not knowing if anyone was doing anything.

I’ve never been so glad to walk away from a story.