The Naspers spinoff hopes to become a global food delivery leader

Prosus Ventures last week filed a hostile offer for British food delivery startup Just Eat, an attempt to defeat a unanimous rejection from its board and simultaneously fend off a bid from rival Takeaway.

The giant Naspers spinoff said it was willing to pay as much as $6.3 billion in cash to lure Just Eat, one of Europe’s largest foodtech players.

Prosus’ major bet on online food startups shouldn’t come as a surprise; the recently-listed subsidiary, whose parent firm has invested in companies in more than 90 nations, has shown a great appetite for food delivery startups globally.

How deeply Prosus believes in foodtech is perhaps on display in emerging markets such as India, one of the most buzziest nations for the investment firm, where the unit economics doesn’t work yet for almost any internet startup and probably won’t for another few years.

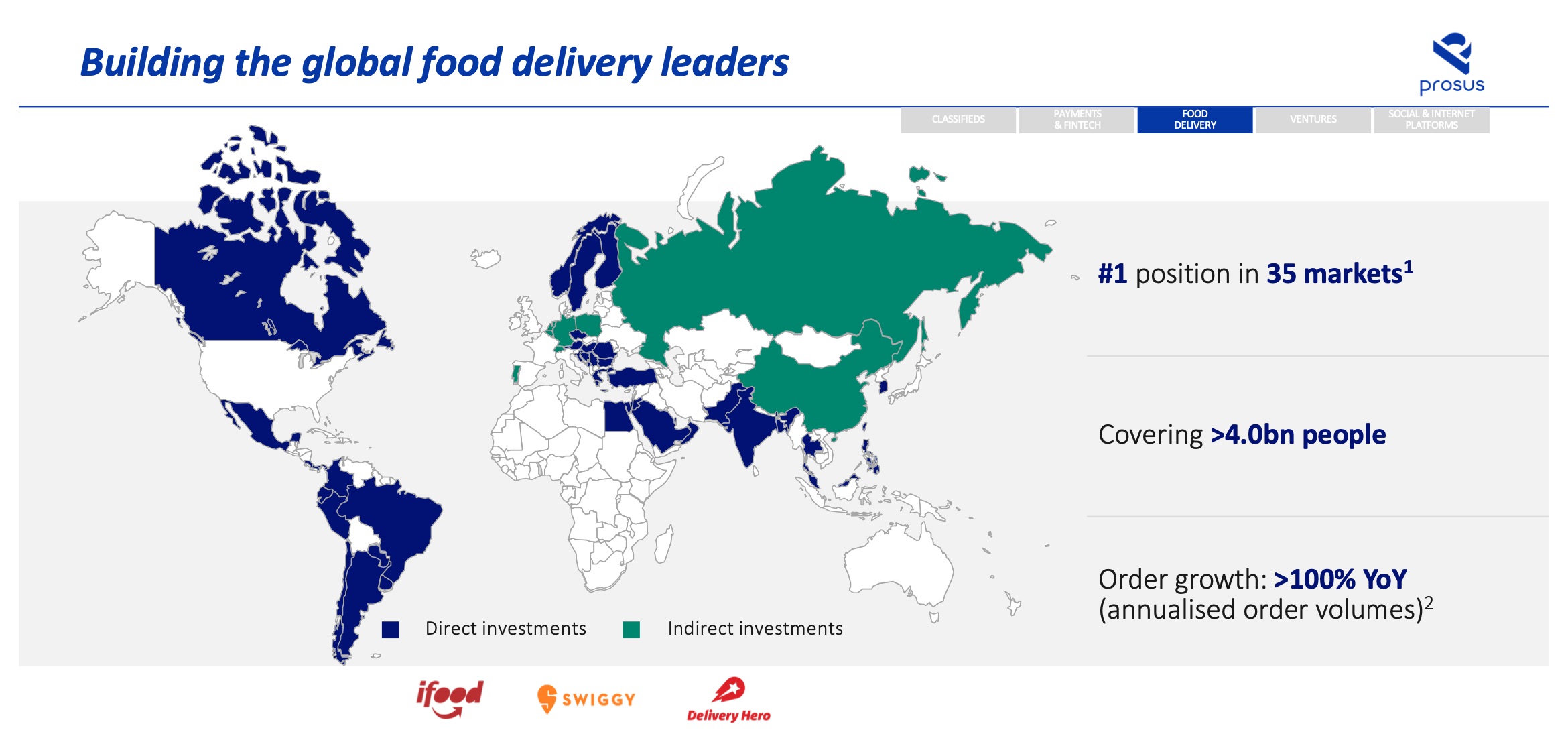

Prosus Ventures’ investments in food delivery startups globally

Last year, South Africa-based Naspers led a $1 billion financing round for Indian food delivery startup Swiggy. The investment firm contributed $716 million to the round, just shy of the roughly $750 million that Swiggy’s chief rival, Zomato, has raised in its 11 years of existence.

TechCrunch spoke with Larry Illg, CEO of Prosus Ventures and Food, and Ashutosh Sharma, head of investments for India at the venture firm, to understand how significant foodtech is for the investment firm and the bets it is making in India.

Swiggy

“We had a thesis on food delivery globally,” said Illg, describing the company’s first search for a food delivery company in India. “We knew that at least one big player will be there in India in the future. We went around the town and spoke to a lot of startups.”

And then they found Swiggy. But, Illg said, it was a very different Swiggy from the one that currently dominates the Indian market. “So here was a food delivery startup that was already profitable. The only challenge was that it was operational in just six cities in India.”

And thus began Naspers’ journey to convince Swiggy to expand its service nationwide. Now operational in more than 130 cities around the country, Swiggy today competes with Zomato, UberEats, and Ola-owned FoodPanda (now known as Ola Foods).

Prosus Ventures’ Sharma, who heads India business, cautioned that it is early for food startups in India. “I want to say we are on day one, but it might as well be day zero. The number of smartphone users in India who are ordering food online is still less than 2%,” he said.

But even this nascent category has attracted some tough competitors. While UberEats and Ola’s Foods are struggling to make a significant dent, Swiggy and Ant Financial-backed Zomato are locked in an intense battle.

Both companies, according to industry reports, are losing more than $20 million each month. Zomato was burning about $45 million each month a year ago, Info Edge, a publicly-listed investor in the startup revealed in its recent earnings call with analysts.

Illg is not really bothered with the frenzy cash burn in India’s food delivery market, and said Prosus has no shortage of cash, either.

That cash might come in handy very soon. A source at Zomato told TechCrunch that the company is in talks to raise as much as $550 million in a round led by Ant Financial .

TechCrunch reported earlier this year that Zomato is quietly setting up its own supply chain to control the raw material its restaurant partners use. Two sources familiar with Zomato say the food delivery startup is thinking of expanding beyond delivering food items.

Earlier this year, Swiggy announced that its delivery fleet can now move just about anything from one part of the city to another. The service, called Swiggy Go, is currently limited to select cities. Zomato plans to replicate this, sources say. Neither of these developments have been previously reported.

Additionally, cloud kitchens are current area of focus for Swiggy. This week, the company announced it has established more than 1,000 cloud kitchens in the country, more so than any of its rivals.

Illg said cloud kitchens are crucial for a country like India, which has a low density of restaurants. “We have the visibility of all the market dynamics,” he said. “We can look at a location, comb through the data and know what kind of restaurants and food supplies would work there.”