Paul Brest didn’t set out to transform philanthropy. A constitutional law scholar who clerked for Supreme Court Justice John Harlan and is credited with coining the term “originalism,” Brest spent twelve years as dean of Stanford Law School.

But when he was named president of the William & Flora Hewlett Foundation, one of the country’s largest large non-profit funders, Brest applied the rigor of a legal scholar not just to his own institution’s practices but to those of the philanthropy field at large. He hired experts to study the practice of philanthropy and helped to launch Stanford’s Center for Philanthropy and Civil Society, where he still teaches.

Now, Brest has turned his attention to advising Silicon Valley’s next generation of donors.

From Stanford to the Hewlett Foundation

Scott Bade: Your background is in constitutional law. How did you make the shift from being dean at Stanford to running the Hewlett Foundation as president?

Paul Brest: I came into the Hewlett Foundation largely by accident. I really didn’t know anything about philanthropy, but I had been teaching courses on problem-solving and decision making. I think I got the job because a number of people on the board knew me, both from Stanford Law School, but also from playing chamber music with Walter and Esther Hewlett.

Bade: When was this?

Brest: I started there in 2000. Bill Hewlett died the year after I came. Walter Hewlett, Bill’s son, was chair of the board during the entire time I was president. But it’s not a family foundation.

Bade: What were your initial impressions of the foundation and the broader philanthropic space?

Brest: Not having come from the non-profit sector, it took me a year or so to really understand what it [meant] to use our assets in each area in a strategic way. The [Hewlett] Foundation had very good values in terms of the areas it was supporting — the environment, education, population, women’s reproductive rights. It had good philanthropic practices, but it was not very strategically focused. It turned out that not very many foundations were strategic.

Paul’s framework for thinking about philanthropy

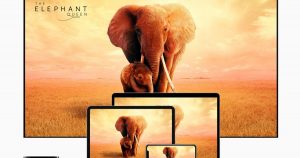

Photo provided by Paul Brest

Bade: What do you mean by ‘strategic’?

Brest: What I mean [by] strategic is having clear goals and having an evidence-based, evidence-informed strategy for achieving them. Big foundations tend to be conglomerates with different programs trying to achieve different goals.

[Being strategic means] monitoring progress as you work towards those goals. Then evaluating in advance whether the strategy is going to be plausible and then whether you’re actually achieving the outcomes you’re trying to achieve so that you can make course corrections if you’re not achieving.

[For example,] the likelihood that the roughly billionaire dollars or more that have been spent or committed to climate advocacy are going to have any effect is quite low. The place where metrics comes in is just having kind of an expected return mindset where yes, the chances of success are low, but we know that the importance of success — or putting it differently, the effects of failure — are going to be catastrophic.

What a strategic mindset does here is say: it’s worth taking huge bets even where the margins of error of the likelihood of success are very hard to measure when the results are huge.

I don’t want to say the [Hewlett] Foundation was anti-strategic, or totally unstrategic, but it really had not developed a [this kind of] systematic framework for doing those things.

Bade: You’re known in the philanthropic community for putting an emphasis on defining, achieving, measuring impact. Have those sort of technocratic practices made philanthropy better?

Brest: I think you have to start by asking, what would it mean for philanthropy to be good? From my point of view, philanthropy is good when I like the goals it chooses. Then, given a good goal, when it is effective in achieving that goal. Strategy really has nothing to say about what the goals are, but only how effective it is.

My guess is that 90 plus percent of philanthropy is intended to achieve goals that most of us think are good goals. There are occasions when you have direct conflicts of goals as you do with say the anti-abortion and the choice movements, or gun control and the NRA. Those are important arguments.

But most philanthropy is trying to improve education or improve the lives of the poor. My view is that philanthropy is good when it is effective in achieving those goals, and trying to do no harm in the process.