Flu season is good for no one. The infection kills thousands of people every year, while many more spend days suffering in bed. Kids get infected. Then the virus flattens the parents who stay home with them. Even dogs are laid low.

Except there is one entity that kinda loves the flu. Telemedicine companies are hoping to use the annual scourge as a lure for new customers. When the days get shorter and the germs run rampant, they start to see more users checking out their services. With this year’s flu season off to an early and virulent start, 2020 is shaping up to be good for business.

The idea now filling Powerpoints is this: A flu-sickened patient, either unable or unwilling to see a regular doctor, schedules a quick video checkup, loves the experience, and then comes back for more medical care on demand. Dermatology exams, therapy, pink eye—just stay home and turn on the camera.

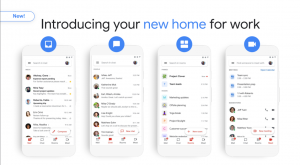

Telemedicine isn’t new; the dated sound of the term reveals its decades-old promise. Yet the technology is perhaps, finally, finding a niche. Tech companies eased the transition by training people to take care of a growing list of needs from home. Skip the grocery run and just use Instacart. Looking for the newest Scorcese flick? It’s cued up on Netflix. Thanks to Slack, Zoom, and Google, your office dress code can be a bathrobe and slippers. It’s only fitting that the same thinking should apply when you’re feeling crummy: Just dial up the doc and chill.

But as with the rise of Amazon and its ilk, what we gain in convenience gets counterbalanced by losses elsewhere. Using virtual medicine companies like Teladoc, Doctors on Demand, or MDLive, patients can get an appointment faster than they otherwise might. More patients might then take Tamiflu, an antiviral that can speed up recovery but that needs to be prescribed within 48 hours of symptom onset. Keeping patients at home is also good for containing the spread of germs. And if virtual visits cover the less critical cases, doctors can more readily attend to very sick patients, says Steve Cashman, an executive at InTouch, which helps outfit hospitals and health systems with the technology they need for video consults.

To a degree, the gospel of long-distance doctoring seems to be working. “We are seeing rapid growth in the use of telemedicine,” says Ateev Mehrotra, a doctor and public health expert at Harvard. “Roughly 50 percent growth year over year.” On its busiest day this year, Teladoc says it saw more than 10,000 patients; collectively these services tend to millions of people a day. Still, of the total number of doctor’s visits, that’s “a tiny fraction,” says Lori Uscher-Pines, a healthcare researcher at the RAND Corporation.

The bigger question, says Mehrotra, is what the switch to virtual care amounts to. With the flu, most of the time there isn’t much that any doctor can do for you. It’s frustrating and annoying but, he says, “you just need rest, mom’s chicken soup, and you’re going to get better.” At most, a doctor’s reassurances might make you feel slightly better in the moment. So do virtual check-ins actually make a difference?

That’s the big unknown now facing healthcare economists. “What we find is that most telemedicine visits are people who would otherwise have stayed home,” says Mehrotra. If that trend means more people seek preventive care, it could end up saving the healthcare system money. But a bunch of new visits, even virtual ones, also means a bevy of new bills that someone has to pay.