Exploring a distant moon usually means trundling around its uniquely inhospitable surface, but on icy ocean moons like Saturn’s Enceladus, it might be better to come at things from the bottom up. This rover soon to be tested in Antarctica could one day roll along the underside of a miles-thick ice crust in the ocean of a strange world.

It is thought that these oceanic moons may be the most likely on which to find signs of life past or present. But exploring them is no easy task.

Little is known about these moons, and the missions we have planned are very much for surveying the surface, not penetrating their deepest secrets. But if we’re ever to know what’s going on under the miles of ice (water or other) we’ll need something that can survive and move around down there.

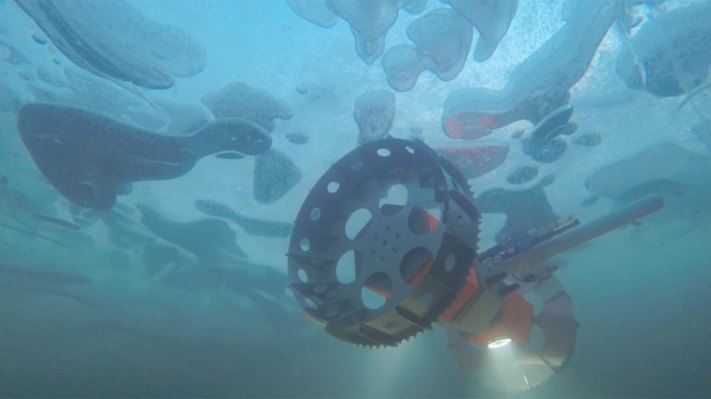

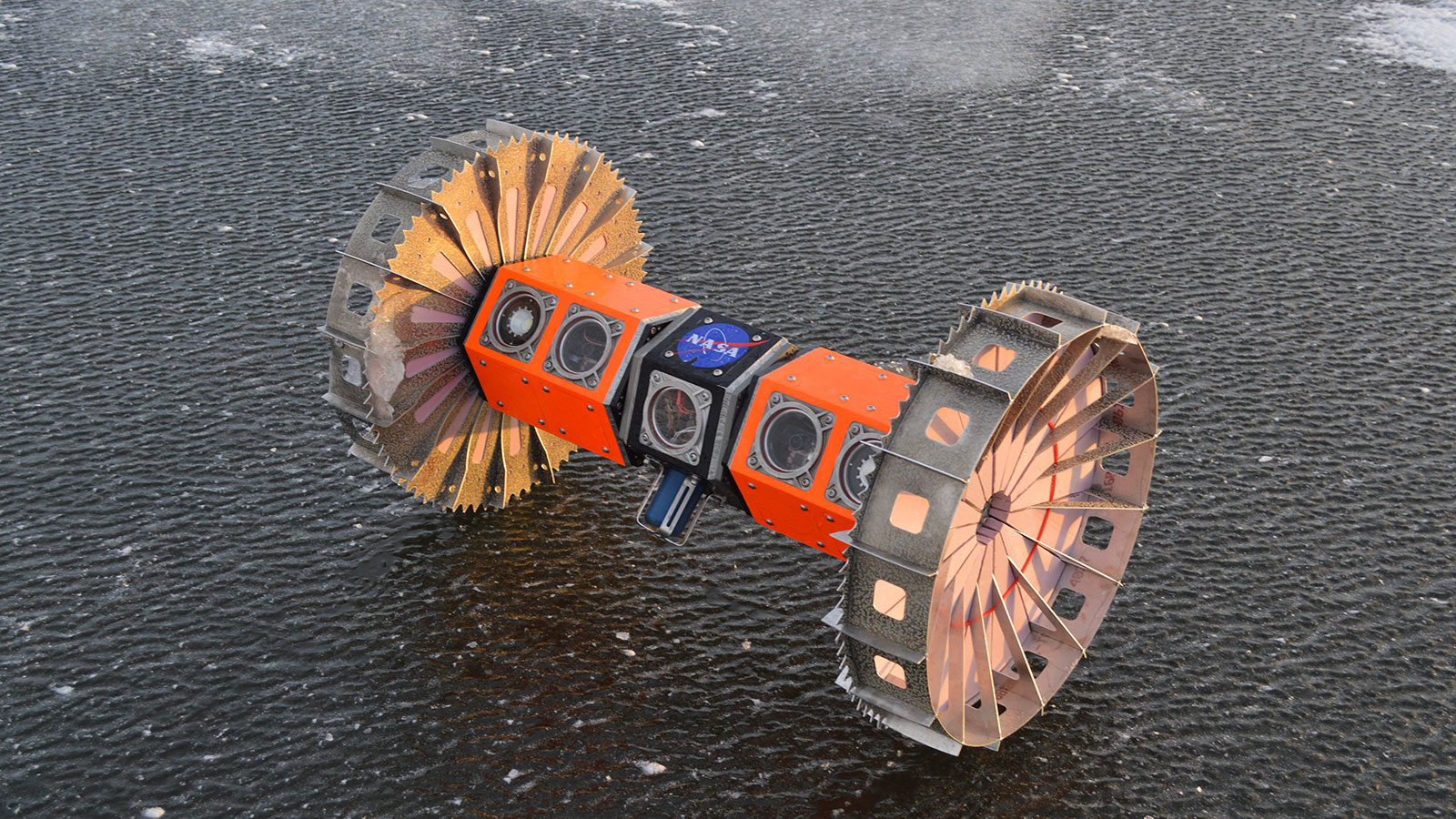

The Buoyant Rover for Under-Ice Exploration, or BRUIE, is a robotic exploration platform under development at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Pasadena. It looks a bit like an industrial-strength hoverboard (remember those?), and as you might guess from its name, it cruises around the ice upside-down by making itself sufficiently buoyant to give its wheels traction.

“We’ve found that life often lives at interfaces, both the sea bottom and the ice-water interface at the top. Most submersibles have a challenging time investigating this area, as ocean currents might cause them to crash, or they would waste too much power maintaining position,” explained BRUIE’s lead engineer, Andy Klesh, in a JPL blog post.

Unlike ordinary submersibles, though, this one would be able to stay in one place and even temporarily shut down while maintaining its position, waking only to take measurements. That could immensely extend its operational duration.

While the San Fernando Valley is a great analog for many dusty, sun-scorched extraterrestrial environments, it doesn’t really have anything like an ice-encrusted ocean to test in. So the team went to Antarctica.

The project has been in development since 2012, and has been tested in Alaska (pictured up top) and the Arctic. But the Antarctic is the ideal place to test extended deployment — ultimately for up to months at a time. Try that where the sea ice retreats to within a few miles of the pole.

Testing of the rover’s potential scientific instruments is also in order, since in a situation where we’re looking for signs of life, accuracy and precision are paramount.

JPL’s techs will be supported by the Australian Antarctic Program, which maintains Casey station, from which the mission will be based.