It’s 11:16 am on a Saturday, and Jack Conte—bright-eyed, bushy-bearded—is zigzagging around a cramped Los Angeles recording studio, dodging eight musicians, two cameramen, a sound engineer, and a profusion of instruments, cords, and mic stands. “Let’s do it!” he cries out, sounding martial and chipper at once, like a high school drama teacher. Conte’s been here since 9 am, leading everyone through a packed day of recording. When the clock strikes 11:17 and the doing-it has yet to commence, he cries out again, “Let’s do it, let’s do it, let’s go!”

Together with his wife, the singer-songwriter Nataly Dawn, Conte is one-half of a band called Pomplamoose. They’ve spent 11 years together building an online following, mostly on the strength of their idiosyncratic, hyper-proficient pop covers—Lady Gaga’s “Telephone” featuring eight-part harmonies, a xylophone, and a toy piano (9.5 million YouTube views); Beyoncé’s “Single Ladies” arranged for upright piano, jazz bass, and an old Polaroid camera repurposed as a percussion instrument (11 million views). When they started out, Conte worked on the band full-time; he and Dawn would usually play all the instruments themselves. They also did all the arranging, filming, and editing. Making one video could take a week.

But then Conte got a high-powered day job working in tech, and to keep their following alive, he and Dawn had to start squeezing an elaborate and intense production routine into the crevices of his schedule. Though they live in the Bay Area, these days the couple flies to LA, where session musicians are plentiful, to crank out music as Pomplamoose. “We come down here once a month and record four songs,” Conte says. “It’s a production flow—an assembly line.” They book eight-hour blocks of studio time, invite a rotating cast of musicians, and pay some guys to film and edit footage. This allows them to post one video per week to YouTube, for a total of 52 per year. It’s not an arbitrary regimen: “YouTube’s algorithm promotes channels that are releasing frequent content,” Dawn explains. “It’s tricky because you have to take the algorithm into consideration—otherwise you aren’t being a smart businessperson—but it changes frequently enough that you can’t just chase algorithms, either.” She thinks for a second. “I mean, you could, but we’re artists.”

It’s this exact tension, between artistry and algorithm-chasing, that drew Conte, 35, into tech in the first place. In 2013 he became cofounder and CEO of Patreon, an online crowdfunding platform. Since then, his company has become one of the most significant players in the frenetic, almost alchemical (which is to say possibly doomed) quest to convert digital creative work into a reliable paycheck for those who produce it.

Patreon sprang directly from Conte’s firsthand experience as a musician trying to make a career on YouTube between 2006 and 2013, a period marked, for Pomplamoose, by brief financial success and then a vortex of rapidly diminishing returns and meager ad-revenue-sharing agreements. As he saw his income dwindle, though, Conte spied a potentially lucrative market in the weird, quasi-intimate relationship between online creators and their most passionate fans. And from that recognition, Conte formalized a new model for supporting creative labor.

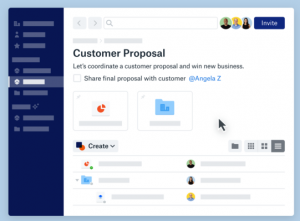

Here’s how Patreon works: You, a creator in search of funds, keep producing and distributing things wherever you usually do—Medium, SoundCloud, YouTube, whatever. But you also set up a Patreon page and direct your fans there in the hope that they will become your “patrons,” committing themselves to recurring monthly payments. (Unlike on Kickstarter, where supporters pitch in toward the completion of an individual project, on Patreon the money goes toward a creator’s ongoing output and livelihood generally.) In turn, Patreon encourages creators to treat these patrons less like charitable benefactors and more like members who have purchased admission to a club—entitling them to exclusive perks, whether it’s gated chat sessions, bonus content, or early peeks at a work in progress. The company makes money by taking a cut from all this fan-to-creator commerce. Patreon’s most recent valuation, in 2017, put the company’s worth at $450 million, but in 2019 both TechCrunch and Forbes have estimated that it is approaching $1 billion—which is also the total sum Patreon says it will have sent to creators by year’s end.

Today Patreon’s ranks are full of musicians, podcasters, gamers, animators, illustrators, authors, photographers, and the like, and Conte’s ambitions for the company have grown—as Silicon Valley ambitions have a way of doing—into a promise of sweeping societal change. His goal, which festoons Patreon’s marketing copy, is nothing less than to “fund the creative class.” He has prophesied that “we’re going to get so good at paying creators, within 10 years, kids graduating high school and college are going to think of being a creator as just being an option—I could be a doctor, I could be a lawyer, I could be a podcaster, I could have a web comic.”

Conte is tall and lanky, with a broad smile and a voluminous smokestack of facial hair. Bald up top, he tends toward baseball caps—right now in LA it’s a beige one embroidered with the silhouette of Kokopelli, the Native American flute-playing deity. For Conte, these marathon Pomplamoose recording sessions represent a lively engineering challenge: “It’s a fun problem, and a different problem than being an artist—it’s systematizing and scaling media production.” If things click along as planned, each song takes exactly two hours—“an hour to arrange, an hour to record.” So far this morning, they’re more or less on track: The band has already wrapped one number, a loungey cover of Daft Punk’s “Something About Us.” Next up is what Dawn calls “the most complicated song” on the agenda, incorporating a full string quartet: Randy Newman’s “You’ve Got a Friend in Me.” They chose it, she notes, because “the new Toy Story is coming out soon” and Pomplamoose is hoping to piggyback on a spike in searches for the song.

Conte plants himself at a Fender Rhodes keyboard and checks in with one of today’s guest musicians, a YouTube violinist of some prominence. Her name is Taylor Davis; she has 2.7 million subscribers, and her presence in this video should help further juice its SEO potential while sending some of Pomplamoose’s approximately 760,000 subscribers her way. Not that Conte phrases it anywhere so crassly: “She’s this amazing violinist I was a fan of,” he says, “and apparently she was a fan of Pomplamoose.”

At 11:27 Dawn sets up in a vocal booth, and they begin hashing out the cover. As an arranger, Conte likes to sprinkle in a variety of styles and techniques, the better to hold a viewer’s attention. A pulsating “hocketing” effect gives way to “a super quiet tremolo vibe” gives way to “Stravinskyish pulses.” Suggesting and soliciting ideas, he speaks in jazz-hepcat lingo one moment (“Hey, B-Green, do you wanna take chugs and I’ll find holes?”), then lapsing into software-developer vernacular the next (“For v1, how about …”). The mood in the room is cheerfully businesslike. When someone does something Conte isn’t crazy about, he says “That’s the right instinct,” before nudging them in another direction. When he’s happy, he signals his enthusiasm with an extravagance that can feel disproportionate: At one point the drummer, Ben Rose, supplies an impromptu cowbell accent, and Conte throws back his head in a show of delight so forceful that his headphones go flying.

By 1:30 pm they’ve got the cover in the can. “This is so fun!” Conte declares. Which means it’s time for a lunch break—a quick one, scarfed standing up, because now they’re running behind and there are still two songs to get through.

Jack Conte.

Photograph: Michelle GroskopfOn a warm Tuesday evening a month later, Conte opens the gate to the East Bay home he shares with Dawn and their rescue dog, Muppet. The property, which they moved into last summer, is composed of two newly renovated buildings and an interior courtyard—one building contains their home studio, and the other is where they live. Conte shows me the second-story studio. “This is my favorite place in the world,” he says. “This is a 1970s Rhodes. This is a 1970s Wurly—a Wurlitzer 200, a classic old keyboard, Ray Charles, you name it. This is a real Hammond organ,” he says, pausing to tap out a bubbling riff, which sounds beautiful. “I got it from a woman who played at church.” Patently less charming, but of comparable importance, is a cluster of video production gear on the far wall: “We got the vlogging lights ready to go,” he says, flicking on a pair of blinding Kino Flo LED rigs mounted above what he calls his “YouTube camera setup”: tripod, mic, four-figure Canon EOS.

This studio is a long way from the makeshift one, across the Bay in Corte Madera, that Conte’s earliest fans first saw circa 2006, when he started uploading videos from his childhood bedroom. A recent college graduate at the time, Conte had moved back in with his dad while he tried to gain traction as an artist. Thanks to his father, music’s been part of Conte’s life for as long as he can remember. “When I was 6 my dad taught me the blues scale, and I started writing songs and improvising,” he recalls. An epidemiologist at UC San Francisco, Conte’s father played jazz piano as a hobby. “He had a band called the Jazz Doctors,” Conte tells me. “All doctors at UCSF: a neurosurgeon, a gastroenterologist …” I can’t help but observe that a jazz group composed of doctors called Jazz Doctors is extremely dorky. “So dorky!” Conte says, beaming. His mother, a nurse, liked to sing, and together his parents played standards in the living room while Conte and his older sister watched.

Conte’s teenage musical tastes were not cool in any conventional sense. He joined his high school jazz combo. He had a thing for film scores (“I loved the Sister Act 2 soundtrack”), and he revered the virtuoso jazz pianist Brad Mehldau (still does). Describing his favorite music, he’s analytical in a way that makes his eventual transition into tech seem more probable: “There were certain types of chords and chord structures and sounds I liked, and they were consistent,” he says, whether he was listening to jazz, classical, pop, or electronic music: “It was mode mixture, chords where there’s a sharp 4 in the melody. It’s kind of regal-sounding, it sounds important.”

In 2002 Conte enrolled at Stanford, where he met Dawn at a campus coffee shop. Raised in France and Belgium by religious academics, Dawn played Christian rock in her teens, and as a Stanford undergraduate she majored in art before getting her master’s in French literature. Conte, for his part, thought he might study filmmaking, then physics, but he decided to stick with his earliest passion, majoring in music. He did so under the auspices of Stanford’s avant-garde-leaning Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics, but Conte’s preferences tended to the more readily intelligible, albeit with stylistic curveballs thrown in. “I really like incorporating noise music into pop,” he says. “Kid A is my favorite record.”

Nataly Dawn.

Photograph: Michelle GroskopfConte’s college roommate, Sam Yam, tells me that amid a sea of fellow students intent on becoming tech impresarios and investment bankers, Conte stood out for his devotion to oddball creativity. Yam recalls the elaborate claymation sets Conte constructed in their dormitory, for music videos and other larks. After graduation, Yam says, “I think we synced up a few times, but basically I viewed him as being a mini-celebrity on YouTube.”

Conte tried traditional musical avenues at first, like café open mics. But he was early to see the potential of YouTube, and there he was able to build a sizable fan base and eventually earn a living—thanks to videos marked by SEO savvy and winningly homemade aesthetics. Conte liked to film each individual bass pluck and conga slap that went into a given song, editing these together into kinetic documents of the recording process. He and Dawn routinely performed barefoot in pajamas, and their central dynamic on camera, then and now, calls to mind a mismatched classic-comedy duo: Dawn musters the low-affect cool of a ’60s chanteuse, preferring to hold still with her eyes wide and unblinking, while Conte mugs for the camera and bounces around a lot. To broaden Pomplamoose’s audience, the duo specialized in pop covers, which appeared high in search results and drove people to iTunes to purchase Pomplamoose’s songs. They began selling merch, including grapefruit-scented soap that Conte’s sister made. (The French word for grapefruit is pamplemousse.) “The soap sold like hotcakes. It was one of the first times we realized, there’s economic power behind this,” Conte says. “There’s a community—and there’s value here.”

In the late 2000s, converting their view count into ad revenue, soap sales, iTunes downloads, product placement deals, live gigs, and even a commission from Hyundai to make commercials, Conte and Dawn made enough money to buy a house in rural Cotati, California, and make music full-time. But it was a precarious livelihood: Early on, Pomplamoose made as much as $60,000 per year by sending viewers to download its songs on iTunes. Then Spotify came along and decimated that model, replacing all that download income with a mere $6,000 in streaming income. They were circling the drain toward which all media flowed in the early teens: paltry ad-revenue-sharing deals with giant platforms.

Around the start of 2013, Conte got back in touch with Yam. In the years since graduation, Yam had founded and sold a mobile advertising platform, AdWhirl, and made a bunch of industry connections. “Jack told me he’d had this idea bubbling in his mind, and he was a little paranoid about the process of building a company,” Yam remembers. Conte wanted to discuss his scheme but asked whether they ought to sign a nondisclosure agreement with each other first. Yam dismissed this caution as the jitters of a tech neophyte. “I was like, ‘Jack, the ideas don’t matter at all—it’s how you execute them,’ ” he says. “So we met up at Coffee Bar, in the Mission, and he shared the idea.” And Yam promptly reversed himself: “I was like, ‘Don’t tell anyone! I’m gonna start building it tonight.’”

Conte and Dawn in their home recording studio.

Photograph: Michelle GroskopfNear the entrance of Patreon’s San Francisco office, a giant piece of art dominates one wall. It’s a black and gray spray-painted assemblage of electrical outlet faceplates, wire caps, washers, vents, and other hardware-store detritus that Conte glued together at home to serve as the backdrop for a 2013 music video. His goal was to re-create the cockpit of the Millennium Falcon. In Patreon mythology, this DIY cockpit functions like the proverbial Silicon Valley garage: the humble, unlikely setting from which a world-changing idea was born. “This is how it all began,” Patreon’s head of communications says.

In late 2012, the story goes, Conte started to become obsessed with making a blowout video for an up-tempo solo track he’d written called “Pedals.” The video would feature not only the Millennium Falcon facsimile but also two singing and dancing automata borrowed from roboticists in Arizona and Britain. According to a behind-the-scenes vlog, Conte worked “16-hour days for 50 days straight” to construct the set, shooting the video over three 19-hour days starting on February 18, 2013. He sank more than $10,000 into the project, maxing out two credit cards.

In some accounts he’s given, the light bulb moment for Patreon arrived during the set-building process. In other accounts, Conte is fuzzier with the timeline: “My hands were, like, broken and bloody and cut up at the end of this,” he recalled in a 2017 Recode interview. When he sent the video out to fans, he continued, “they went crazy about it, and then you’d see your YouTube dashboard, you’d see $150”—referring to his paltry share of ad revenue—“and I just. I lost it. I just. That’s it. You can’t. It’s so demoralizing as an artist to feel so successful, and to have such a discrepancy between the impact you feel you’re having on the world and then the paycheck that you get at the end of the month.” Patreon, he says, sprang from his exasperation. “It was this rock-bottom moment for me as a creator,” Conte told Forbes last year.

All in all, “Pedals” illustrates something beyond Conte’s ingenuity and grit as a bedroom video auteur: his canniness, from the start, when it came to Silicon Valley narrative-building. Yam tells me that months before Conte finished the “Pedals” video, he had come to envision it as a kind of loss leader for Patreon. The ordeal of making it, he realized, would serve as a splashy illustration of the problem his new company promised to tackle—the gross imbalance between the work creators put into digital platforms, the number of views that work generated, and the revenue they got in return. And the video’s release on YouTube would help publicize Patreon’s debut. During the roughly three months that Yam worked to code the Patreon site, he says, Conte worked on finishing the video. “There was no way he was going to recoup the $10,000 from advertising, so he was putting his bet on this working out,” Yam recalls. As for the expenses Conte personally poured into the video, Yam adds that Patreon “reimbursed those afterward.” Uploaded on the same day Patreon launched, “Pedals” was a business expense presented as a labor of love. In its final moments, Conte addresses the camera directly, asking fans to check out his brand-new artist page on his brand-new site, Patreon.com.

Six years later, who does Patreon serve best? Some 125,000 creators use the service, and according to the data-tracking site Graphtreon, they draw in more than 5 million pledges monthly. One of Patreon’s top-earning clients, grossing $139,000 monthly from 31,000 patrons, is the bitingly funny leftist-politics podcast Chapo Trap House, whose cohost, Will Menaker, has praised Patreon’s small-donor model as essential to the show’s existence and integrity. (Thanks to Chapo‘s patrons, no Dollar Shave Club ads need interrupt the socialism.) The most popular musician on Patreon is the extremely online singer-songwriter Amanda Palmer, who has more than 15,000 patrons and doesn’t disclose her earnings.

In predicting whether an artist will succeed on Patreon, Conte says, “the most important thing isn’t media or genre or platform—it’s how much do you love your fans, and how do they love you back? Are you making a thing that gives people all the feels, and do they just fucking love you?” This is not strictly a matter of artistic merit. “I don’t think Björk would do well on Patreon,” he explains. “Arguably, her fans think she makes great art. But does she love her fans, and do they love her back? I don’t know.” By and large, he says, Patreon privileges those creators who tend toward higher-frequency output and whose fans regard them as (mistake them for?) dear friends. “Amanda Palmer loves her fans and they love her,” Conte adds. “They actually feel love for her. That’s a particular type of artist. Not every artist wants that vulnerable, close, open relationship with their fans. Like, really tactically: Do you run fan-art contests? Do you respond to comments on Twitter? Do you sell soap—do a weird fun thing with your fans then send them a thing in the mail, thanking them for what they contributed?” If not, don’t count on making your rent via Patreon.

In many ways, Conte is still figuring out how to transform from Pomplamoose Jack into CEO Jack. This process has involved “three executive coaches” and all kinds of growing pains that correspond, roughly, to Patreon’s own evolution as a global audience-management service. These days, the range of people who want to cultivate audiences on Patreon extends far beyond bedroom musicians. They also include more controversial and ideologically charged creators, like the makers of a new Jeffrey Epstein-focused podcast called TrueAnon (2,600 patrons contributing $11,000 a month to support the hosts “in capturing the pedo elites”) or the right-wing online magazine Quillette (2,100 patrons contributing $15,000 monthly). Which means that the basic question he once invoked as the company’s true north—“What would Jack Conte want out of this platform?”—has grown less useful.

It also means that Patreon has faced many of the same content moderation dilemmas that have vexed much larger platforms like YouTube and Facebook. The company’s system for reporting abuse, for example, has at times become a shooting gallery for online agitators seeking to defund their political enemies. Within the span of a week in 2017, Patreon shut down the accounts of both a far-right Canadian YouTuber named Lauren Southern and an anarchist news site called It’s Going Down; both had been the targets of coordinated campaigns flagging them for violations of Patreon’s community guidelines.

Predictably, Conte’s attempts to run a neutral platform have pleased no one. People on the left accused Patreon of shuttering It’s Going Down just for the sake of balance, to appease trolls on the right. And last December, after Patreon booted another right-wing account for violating community guidelines against hate speech, prominent right-leaning figures like Jordan Peterson and Sam Harris left the platform in protest of its supposed left-leaning political bias. “It’s not a matter of politics for me, to be super clear,” says Conte, who was vocal on Twitter during 2016 in his distaste for Donald Trump. “We’ve taken down ultra-left groups for the same reasons as ultra-right.” All communities set rules, he says. “The difference is scale. When your community is 2 billion people, and your decisions affect the global consciousness, these decisions shouldn’t feel arbitrary.” A funny riff on a toy piano, this is not.

SIGN UP TODAY

Sign up for our Longreads newsletter for the best features and investigations on WIRED.

Conte has also struggled to avoid alienating his core users as he chases new revenue and brings his platform up to scale. In March—partially in response to Facebook’s launch of a distinctly Patreon-ish product called Fan Subscriptions—Patreon announced that it was scrapping its longtime policy of collecting a flat 5 percent of the income creators got from their patrons. Now, in addition to a bare-bones Lite plan at 5 percent, it would restrict certain features and services to creators willing to pay for Pro and Premium accounts, topping out at a 12 percent take. In response to this fee hike, a popular YouTuber named Dan Olson posted a thread on Twitter arguing that the greed of the company’s venture capital backers had finally kicked in: “Investors who demand geometric growth are about to demand Patreon eat itself.” The thread went viral. When I mention it, Conte takes several minutes to list some of the operating costs that Patreon must increase revenue to meet. “I get pressure from VCs, but I get more pressure from creators,” he says. “Creators get furious when we don’t do what they want.” (Facebook’s Fan Subscriptions service, for its part, takes as much as 30 percent.)

On a Thursday afternoon in June, Conte strides into a Patreon conference room for an executive strategy meeting whose overarching theme is how to grow the company faster. Patreon’s offices look every bit the part of the burgeoning tech success circa 2019: poured-concrete everything, phalanxes of free cereal and on-tap beverages, motorized standing desks, bright pennants indicating whether the workers listed below (200 of them in all) work for the legal team or for “community happiness.” But Conte isn’t satisfied with Patreon’s total of 125,000 creators. “Patreon right now has such low market penetration,” he tells me before the meeting. “We’re a speck of dust. We’re not having an impact; we’re not changing the global systems of art and finance yet—and we want to.”

Patreon’s current internal goal is to substantially increase the number of what it calls “1K creators”—those earning at least $1,000 per month from their patrons. But what’s the best way to do that? That’s the question of the hour. Sitting opposite Conte, Wyatt Jenkins, a tattooed former DJ and tech veteran turned Patreon’s head of product, argues that the smart move is to lavish support and attention on creators in somewhat higher monthly earning brackets.

Conte cuts in: “Just to be clear, we’re not talking about changing the KPI”—key performance indicator. “1K creators is the KPI.”

Jenkins nods. “It’s just how we get there,” he says. “I think we have to aim a little upstream and it’ll pull, because the 1Ks wanna be the 5Ks.” There’s a risk, he acknowledges. “The messaging will be super tricky,” Jenkins says, “because the downside of this message is ‘Oh, we don’t care about small creators as much,’ which just isn’t the fact. Of course we care about small creators. But when we build things, we aim at larger creators, and they’re the ones who inspire the smaller creators to do something bigger.”

“I like that,” Conte responds. Then he moves to the next item on the agenda, which continues the theme of how to better serve large accounts on Patreon—and how to lure new ones through the door. The other night, Conte says, he hosted a dinner in Los Angeles for “10 huge creators,” which doubled, informally, as both market research and a sales pitch. Nine of the creators were already on Patreon, and one wasn’t, yet: a YouTuber named Ian Hecox, who, as one-half of the blockbuster comedy channel Smosh, has 25 million YouTube subscribers. Conte says he asked everyone at the dinner a two-part question: What’s a great thing about being a creator right now, and what makes you want to jump off the porch? “So one by one,” he says, “Ian listens to creator after creator talk about how fucking awesome Patreon is and how it’s changed their lives.”

The appeal of enticing someone like Hecox onto Patreon was clear: 25 million subscribers is a lot of potential donors, and a plug from Smosh to “check out our Patreon page” after every video upload would bring a lot of impressions. Conte beams like a salesman bearing down on a monster account. “He’s gonna launch,” Conte predicts.

Conte grew up playing jazz, but his Pomplamoose videos favor inventive pop covers.

Photograph: Michelle GroskopfConte wouldn’t put it this way, but if there’s a villain in the story of Patreon, it’s megaplatforms like YouTube. When he describes how he came to start his company, Conte routinely contrasts his delight in his early days on YouTube with his growing fury at the pittance that site sent his way. According to a slide Conte projected overhead during a 2017 TED talk, in one 28-day period, during which his account generated 1,062,569 views, he received a measly $166.10 payout. In the same talk, he referred to an unnamed author of a web comic who had 20,000 monthly readers but received only “a couple hundred bucks in ad revenue.” For visual reference, he put up a giant image of a basketball stadium packed with 20,000 people. “Like, in what world is this not enough?” he sputtered. “I don’t understand! What systems have we built where this is insufficient for a person to make a living?”

At Conte’s home, we cross the courtyard into the living room, sharing beers and a takeout pie from a nearby worker-owned pizzeria. I bring up Pomplamoose’s monthly trips to LA and, by extension, the pressure that YouTube puts on creators to produce, produce, produce—a pressure that’s come to feel increasingly exploitative for reasons Conte outlines and beyond. In his reply, Conte strikes an initially politic tone: “I used to blame YouTube a lot more than I do now as a person inside a tech company. I have a lot more empathy for technology leaders.”

He is quiet for a moment, then adds, “But.” He taps at his phone and shows me the screen: “This is my app as a YouTube creator. This is the dashboard for Scary Pockets”—a funk side project Conte plays in. “Oh look, I’m having a good month, so I get a little green arrow pointing up. And when my views drop below what I got last month, guess what, I get a little red arrow pointing down. And that’s a little slap on the wrist. ‘Go get more views.’ ” He toggles over to the Pomplamoose account. “It is red for Pomplamoose right now. They slap my wrist a bit. ‘Bad Pomplamoose!’ We’re down to 5.9 million minutes—we got 14,000 new subscribers, but it’s less than we got in the previous 28 days. So we see that red arrow, and we get a little dose of that chemical that makes me feel a little ashamed. Not terrible, but a little ashamed, and—fuck.” Conte frowns. “That sucks as a creative person.”

The problem extends, of course, past insidious design cues. “In a system where watch time equals revenue? The mechanism of advertising that converts attention into dollars? Holy shit, that’s a dangerous conversion, with all kinds of negative downstream effects,” Conte continues. “Because time spent is not representative of what we actually value. It’s representative of our lizard brains’ addictions, and those aren’t things that are necessarily good for us or important to us or beautiful. It’s just things that are getting us to open our eyes. And we’ll open our eyes at a bunch of shit! And we’ll just stay glued to it. So the system that converts attention into dollars and scales it globally, I don’t think that’s the right distribution system for the arts. It’s that simple: Literally, the metric that this giant AI called YouTube wants is watch time, and it’s very powerful. It knows so much. It can do so much, and convince and coerce and manipulate, and it’s doing a really good job.”

In this critique, Conte is persuasive. One adverse effect of the attention economy that people are only starting to reckon with is the problem of creator burnout. In a way analogous to, say, how Lyft and Uber drivers are forced to work ever-longer shifts for volatile, decreasing levels of compensation, online creators speak these days about the stresses of trying to feed an insatiable, algorithm-driven beast. We see a theatricalized version of this unfold at the end of an early Pomplamoose video: Dawn approaches Conte, lying face down on the floor, and informs him that they owe their fans a vlog. “I’m tiiired!” he moans. It’s played for laughs, but the undertones are dark. “I think about this a lot,” Conte tells me. “My first answer is that you gotta know your limit and be an adult about it. That said, the content treadmill?” He exhales. “Oh God. It’s exhausting. Even for someone like me, who has an insane work ethic—I think I’m unique, and still I can’t keep up. We had to build a team! It’s the only way to sustain that pace of creation!”

Which leads to a strange irony about Patreon. The service may very well allow artists to become less beholden to the unpredictable algorithms, turbulent monetization policies, and stingy revenue-sharing of behemoth distribution platforms like YouTube. But in the absence of a viable alternative to those platforms, Patreon winds up effectively subsidizing that very unpredictability, turbulence, and stinginess. Put another way, Patreon promises to make a YouTube creator’s life easier—a patently good thing—but in the process it puts no pressure on companies like YouTube to change the ways it hurts creators in the first place. What this means is that even Patreon’s CEO himself still sees fit to organize one weekend out of every month around the explicit goal of producing content for YouTube.

Conte nods as I float this line of reasoning past him. “If I could think of a way to solve the problem that doesn’t have that negative trade-off, I’d probably do it, but I don’t know how to get past the network effects,” he says. “I don’t know how to rebuild the behavior from the ground up and break the YouTube ecosystem. They have a stranglehold, you know?” I mention the grim trend of people using crowdfunding campaigns to help pay catastrophic medical bills. No one would criticize GoFundMe for facilitating such campaigns—another patently good thing—but they can’t come close, of course, to addressing the root problem, which is a broken health care system. Is Patreon the same kind of band-aid, but for a broken creative market? Conte concedes that “there’s an argument to be made that Patreon doesn’t address some of the negative side effects of the content treadmill and the current ad-driven ecosystems, or that it even finances those behaviors rather than cannibalize them—I think all those things are true.”

Can a single, private company really “fund the creative class”? From the perspective of a healthily functioning society, would that even be desirable? Some questions are too big to answer over pizza. “All you can do is make incremental improvements over long periods of time,” Conte says, “and I think the existence of Patreon is incrementally better than the nonexistence of Patreon.”

His phone buzzes. Tuesday night is garbage night on his block, and he has set a reminder to roll his bins to the curb. He walks me out, passing the stairs to Pomplamoose’s studio. I ask whether he’d like to eventually shift the balance in his life away from Patreon and back to music—back up those stairs to his “favorite place in the world.” “That’s not a goal,” he says. “This is a reckoning for me, but I’m actually—I’m, like, happier now than I was eight years ago, even with Pomplamoose taking off.” For one thing, “there’s things about Patreon I didn’t get with music: the scale of impact.” For another, “being an artist is hard. Personally and emotionally, it’s difficult. There’s a tension that exists as an artist that doesn’t exist as a business. When your fans are like, ‘Yeah, the new stuff is great, but we like this old record,’ and you’re like, ‘I wanna grow as an artist’? That whole dilemma you have between making shit for your fans versus being a real artist? When you have customers who need things, you just fucking make the things they need, and you don’t feel guilty for making them! You don’t have that internal, pulling-my-soul-apart existential self-debate where you’re flogging yourself for doing fan service, or like, making a record that you’re not proud of because it’s what your fans want. That shit is so hard. That’s the I-can’t-sleep-at-night kind of hard.”